Home > Press > How ultracold, superdense atoms become invisible: A new study confirms that as atoms are chilled and squeezed to extremes, their ability to scatter light is suppressed

|

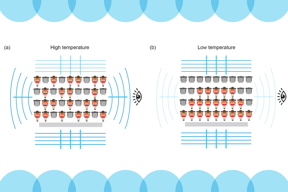

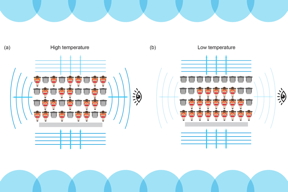

| The principle of Pauli blocking can be illustrated by an analogy of people filling seats in an arena. Each person represents an atom, while each seat represents a quantum state. At high temperatures (a), atoms are seated randomly, so every particle can scatter light. At low temperatures (b), atoms crowd together. Only those with more room near the edge can scatter light.

Credits:Credit: Courtesy of the researchers |

Abstract:

An atoms electrons are arranged in energy shells. Like concertgoers in an arena, each electron occupies a single chair and cannot drop to a lower tier if all its chairs are occupied. This fundamental property of atomic physics is known as the Pauli exclusion principle, and it explains the shell structure of atoms, the diversity of the periodic table of elements, and the stability of the material universe.

How ultracold, superdense atoms become invisible: A new study confirms that as atoms are chilled and squeezed to extremes, their ability to scatter light is suppressed

Cambridge, MA | Posted on November 19th, 2021

Now, MIT physicists have observed the Pauli exclusion principle, or Pauli blocking, in a completely new way: Theyve found that the effect can suppress how a cloud of atoms scatters light.

Normally, when photons of light penetrate a cloud of atoms, the particles can ping off each other like billiard balls, scattering photons in every direction to radiate light, and thus make the cloud visible. However, the MIT team observed that when atoms are supercooled and ultrasqueezed, the Pauli effect kicks in and the particles effectively have less room to scatter light. The photons instead stream through, without being scattered.

In their experiments, the physicists observed this effect in a cloud of lithium atoms. As they were made colder and more dense, the atoms scattered less light and became progressively dimmer. The researchers suspect that if they could push the conditions further, to temperatures of absolute zero, the cloud would become entirely invisible.

The teams results, reported in Science, represent the first observation of Pauli blockings effect on light-scattering by atoms. This effect was predicted 30 years ago but not observed until now.

Pauli blocking in general has been proven, and is absolutely essential for the stability of the world around us, says Wolfgang Ketterle, the John D. Arthur Professor of Physics at MIT. What weve observed is one very special and simple form of Pauli blocking, which is that it prevents an atom from what all atoms would naturally do: scatter light. This is the first clear observation that this effect exists, and it shows a new phenomenon in physics.

Ketterles co-authors are lead author and former MIT postdoc Yair Margalit, graduate student Yukun Lu, and Furkan Top PhD 20. The team is affiliated with the MIT Physics Department, the MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms, and MITs Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE).

A light kick

When Ketterle came to MIT as a postdoc 30 years ago, his mentor, David Pritchard, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics, made a prediction that Pauli blocking would suppress the way certain atoms known as fermions scatter light.

His idea, broadly speaking, was that if atoms were frozen to a near standstill and squeezed into a tight enough space, the atoms would behave like electrons in packed energy shells, with no room to shift their velocity, or position. If photons of light were to stream in, they wouldnt be able to scatter off and illuminate the atoms.

An atom can only scatter a photon if it can absorb the force of its kick, by moving to another chair, explains Ketterle, invoking the arena seating analogy. If all other chairs are occupied, it no longer has the ability to absorb the kick and scatter the photon. So, the atom becomes transparent.

This phenomenon had never been observed before, because people were not able to generate clouds that were cold and dense enough, Ketterle adds.

Controlling the atomic world

In recent years, physicists including those in Ketterles group have developed magnetic and laser-based techniques to bring atoms down to ultracold temperatures. The limiting factor, he says, was density.

If the density is not high enough, an atom can still scatter light by jumping over a few chairs until it finds some room, Ketterle says. That was the bottleneck.

In their new study, he and his colleagues used techniques they developed previously to first freeze a cloud of fermions in this case, a special isotope of lithium atom, which has three electrons, three protons, and three neutrons. They froze a cloud of lithium atoms down to 20 microkelvins, which is about 1/100,000 the temperature of interstellar space.

We then used a tightly focused laser to squeeze the ultracold atoms to record densities, which reached about a quadrillion atoms per cubic centimeter, Lu explains.

The researchers then shone another laser beam into the cloud, which they carefully calibrated so that its photons would not heat up the ultracold atoms or alter their density as the light passed through. Finally, they used a lens and camera to capture and count the photons that managed to scatter away.

Were actually counting a few hundred photons, which is really amazing, Margalit says. A photon is such a little amount of light, but our equipment is so sensitive that we can see them as a small blob of light on the camera.

At progressively colder temperatures and higher densities, the atoms scattered less and less light, just as Pritchards theory predicted. At their coldest, at around 20 microkelvin, the atoms were 38 percent dimmer, meaning they scattered 38 percent less light than less cold, less dense atoms.

This regime of ultracold and very dense clouds has other effects that could possibly deceive us, Margalit says. So, we spent a few good months sifting through and putting aside these effects, to get the clearest measurement.

Now that the team has observed Pauli blocking can indeed affect an atoms ability to scatter light, Ketterle says this fundamental knowledge may be used to develop light-suppressing materials, for instance to preserve data in quantum computers.

Whenever we control the quantum world, like in quantum computers, light scattering is a problem, and means that information is leaking out of your quantum computer, he muses. This is one way to suppress light scattering, and we are contributing to the general theme of controlling the atomic world.

This research was funded, in part, by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense. Related work by a team from the University of Colorado appears in the same issue of Science.

###

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Abby Abazorius

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Office: 617-253-2709

Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology

If you have a comment, please Contact us.

Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

News and information

![]()

Scientists develop promising vaccine method against recurrent UTI November 19th, 2021

![]()

New microscopy method offers 3D tracking of 100 single molecules at once November 19th, 2021

![]()

Visualizing temperature transport: An unexpected technique for nanoscale characterization November 19th, 2021

Quantum Physics

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]()

Scientists develop promising vaccine method against recurrent UTI November 19th, 2021

![]()

Energizer atoms: JILA researchers find new way to keep atoms excited November 19th, 2021

![]()

‘Dancing molecules’ successfully repair severe spinal cord injuries: After single injection, paralyzed animals regained ability to walk within four weeks November 12th, 2021

Possible Futures

![]()

Developing high-performance MXene electrodes for next-generation powerful battery November 19th, 2021

![]()

Efficient photon upconversion at an organic semiconductor interface November 19th, 2021

Quantum Computing

![]()

Quantifying spin for future spintronics: Spin-momentum locking induced anisotropic magnetoresistance in monolayer WTe2 November 5th, 2021

![]()

Photon-pair source with pump rejection filter fabricated on single CMOS chip: New integrated source provides critical component for chip-based quantum photonic systems October 15th, 2021

![]()

Fujitsu and Osaka University deepen collaborative research and development for fault-tolerant quantum computers October 1st, 2021

![]()

Two-dimensional hybrid metal halide device allows control of terahertz emissions October 1st, 2021

Discoveries

![]()

Developing high-performance MXene electrodes for next-generation powerful battery November 19th, 2021

![]()

Efficient photon upconversion at an organic semiconductor interface November 19th, 2021

![]()

New microscopy method offers 3D tracking of 100 single molecules at once November 19th, 2021

Announcements

![]()

Efficient photon upconversion at an organic semiconductor interface November 19th, 2021

![]()

New microscopy method offers 3D tracking of 100 single molecules at once November 19th, 2021

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]()

Scientists develop promising vaccine method against recurrent UTI November 19th, 2021

![]()

Energizer atoms: JILA researchers find new way to keep atoms excited November 19th, 2021

![]()

Developing high-performance MXene electrodes for next-generation powerful battery November 19th, 2021