Home > Press > Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength

|

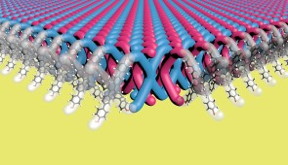

| Credit: Mark Seniw, Center for Regenerative Nanomedicine, Northwestern University |

Abstract:

Resembling the interlocking links in chainmail, novel nanoscale material is incredibly strong and flexible

The interlocked material contains the highest density of mechanical bonds ever achieved

Small amounts of the mechanically interlocked polymer added to Ultem fibers increased their toughness

Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength

Evanston, IL | Posted on January 17th, 2025

In a remarkable feat of chemistry, a Northwestern University-led research team has developed the first two-dimensional (2D) mechanically interlocked material.

Resembling the interlocking links in chainmail, the nanoscale material exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength. With further work, it holds promise for use in high-performance, light-weight body armor and other uses that demand lightweight, flexible and tough materials.

Publishing tomorrow (Jan. 17) in the journal Science, the study marks several firsts for the field. Not only is it the first 2D mechanically interlocked polymer, but the novel material also contains 100 trillion mechanical bonds per 1 square centimeter the highest density of mechanical bonds ever achieved. The researchers produced this material using a new, highly efficient and scalable polymerization process.

We made a completely new polymer structure, said Northwesterns William Dichtel, the studys corresponding author. Its similar to chainmail in that it cannot easily rip because each of the mechanical bonds has a bit of freedom to slide around. If you pull it, it can dissipate the applied force in multiple directions. And if you want to rip it apart, you would have to break it in many, many different places. We are continuing to explore its properties and will probably be studying it for years.

Dichtel is the Robert L. Letsinger Professor of Chemistry at the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and a member of the International Institute of Nanotechnology (IIN) and the Paula M. Trienens Institute for Sustainability and Energy. Madison Bardot, a Ph.D. candidate in Dichtels laboratory and IIN Ryan Fellow, is the studys first author.

Inventing a new process

For years, researchers have attempted to develop mechanically interlocked molecules with polymers but found it near impossible to coax polymers to form mechanical bonds.

To overcome this challenge, Dichtels team took a whole new approach. They started with X-shaped monomers which are the building blocks of polymers and arranged them into a specific, highly ordered crystalline structure. Then, they reacted these crystals with another molecule to create bonds between the molecules within the crystal.

I give a lot of credit to Madison because she came up with this concept for forming the mechanically interlocked polymer, Dichtel said. It was a high-risk, high-reward idea where we had to question our assumptions about what types of reactions are possible in molecular crystals.

The resulting crystals comprise layers and layers of 2D interlocked polymer sheets. Within the polymer sheets, the ends of the X-shaped monomers are bonded to the ends of other X-shaped monomers. Then, more monomers are threaded through the gaps in between. Despite its rigid structure, the polymer is surprisingly flexible. Dichtels team also found that dissolving the polymer in solution caused the layers of interlocked monomers to peel off each other.

After the polymer is formed, theres not a whole lot holding the structure together, Dichtel said. So, when we put it in solvent, the crystal dissolves, but each 2D layer holds together. We can manipulate those individual sheets.

To examine the structure at the nanoscale, collaborators at Cornell University, led by Professor David Muller, used cutting-edge electron microscopy techniques. The images revealed the polymers high degree of crystallinity, confirmed its interlocked structure and indicated its high flexibility.

Dichtels team also found the new material can be produced in large quantities. Previous polymers containing mechanical bonds typically have been prepared in very small quantities using methods that are unlikely to be scalable. Dichtels team, on the other hand, made half a kilogram of their new material and assume even larger amounts are possible as their most promising applications emerge.

Adding strength to tough polymers

Inspired by the materials inherent strength, Dichtels collaborators at Duke University, led by Professor Matthew Becker, added it to Ultem. In the same family as Kevlar, Ultem is an incredibly strong material that can withstand extreme temperatures as well as acidic and caustic chemicals. The researchers developed a composite material of 97.5% Ultem fiber and just 2.5% of the 2D polymer. That small percentage dramatically increased Ultems overall strength and toughness.

Dichtel envisions his groups new polymer might have a future as a specialty material for light-weight body armor and ballistic fabrics.

We have a lot more analysis to do, but we can tell that it improves the strength of these composite materials, Dichtel said. Almost every property we have measured has been exceptional in some way.

Steeped in Northwestern history

The authors dedicated the paper to the memory of former Northwestern chemist Sir Fraser Stoddart, who introduced the concept of mechanical bonds in the 1980s. Ultimately, he elaborated these bonds into molecular machines that switch, rotate, contract and expand in controllable ways. Stoddart, who passed away last month, received the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work.

Molecules dont just thread themselves through each other on their own, so Fraser developed ingenious ways to template interlocked structures, said Dichtel, who was a postdoctoral researcher in Stoddarts lab at UCLA. But even these methods have stopped short of being practical enough to use in big molecules like polymers. In our present work, the molecules are held firmly in place in a crystal, which templates the formation of a mechanical bond around each one.

So, these mechanical bonds have deep tradition at Northwestern, and we are excited to explore their possibilities in ways that have not yet been possible.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Amanda Morris

847.467.6790

Copyright © Northwestern University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.

Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

2 Dimensional Materials

![]()

New 2D multifractal tools delve into Pollock’s expressionism January 17th, 2025

News and information

![]()

Flexible electronics integrated with paper-thin structure for use in space January 17th, 2025

![]()

Quantum engineers squeeze laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

Chemistry

![]()

Breaking carbonhydrogen bonds to make complex molecules November 8th, 2024

![]()

New method in the fight against forever chemicals September 13th, 2024

Law enforcement/Anti-Counterfeiting/Security/Loss prevention

![]()

With VECSELs towards the quantum internet Fraunhofer: IAF achieves record output power with VECSEL for quantum frequency converters April 5th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]()

Quantum engineers squeeze laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

![]()

FSU researchers develop new methods to generate and improve magnetism of 2D materials December 13th, 2024

Possible Futures

![]()

Quantum engineers squeeze laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

![]()

The National Space Society Congratulates SpaceX on Starships 7th Test Flight: Latest Test of the Megarocket Hoped to Demonstrate a Number of New Technologies and Systems January 17th, 2025

Nanotubes/Buckyballs/Fullerenes/Nanorods/Nanostrings

![]()

Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion December 13th, 2024

![]()

Tests find no free-standing nanotubes released from tire tread wear September 8th, 2023

Discoveries

![]()

Quantum engineers squeeze laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

Materials/Metamaterials/Magnetoresistance

![]()

Enhancing transverse thermoelectric conversion performance in magnetic materials with tilted structural design: A new approach to developing practical thermoelectric technologies December 13th, 2024

![]()

FSU researchers develop new methods to generate and improve magnetism of 2D materials December 13th, 2024

![]()

Nanoscale CL thermometry with lanthanide-doped heavy-metal oxide in TEM March 8th, 2024

Announcements

![]()

Quantum engineers squeeze laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

![]()

The National Space Society Congratulates SpaceX on Starships 7th Test Flight: Latest Test of the Megarocket Hoped to Demonstrate a Number of New Technologies and Systems January 17th, 2025

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]()

Flexible electronics integrated with paper-thin structure for use in space January 17th, 2025

![]()

Quantum engineers squeeze laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

Military

![]()

Quantum engineers squeeze laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

![]()

Single atoms show their true color July 5th, 2024

![]()

NRL charters Navys quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024